Apple announced a new initiative at its Spring Forward event yesterday – ResearchKit.

What is ResearchKit? Apple’s SVP of Operations, Jeff Williams, described it as a framework for medical researchers to create and deploy mobile apps which collect and share medical data from phone users (with their permission), and share it with the researchers.

Why is this important? Previously it has proven difficult for research organisations to secure volunteers for research studies, and the data collected from such studies is often collected, at best, quarterly.

With this program, Apple hopes to help researchers more easily attract volunteers, and collect their information far more frequently (up to once a second), yielding far richer data.

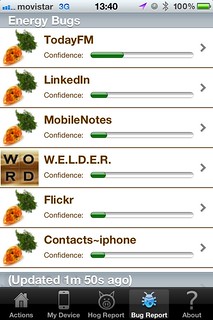

The platform itself launches next month, but already there are 5 apps available, targeting Parkinson’s, diabetes, heart disease, asthma, and breast cancer. These apps have been developed by medical research organisations, in conjunction with Apple.

The success of this approach can be seen already in this tweet:

https://twitter.com/wilbanks/status/575125345977810945

I downloaded mPower, the app for Parkinson’s to try it out, but for now, they are only signing up people who are based in the US.

As well as capturing data for the researchers, mPower also presents valuable information to the user, tracking gait and tremor, and seeing if they improve over time, when combined with increased exercise. So the app is a win both for the research organisations, and for the users too.

Apple went to great pains to stress that the user is in complete control over who gets to see the data. And Apple themselves doesn’t ever get to see your data.

This is obviously a direct shot at Google, and its advertising platform’s need to see your data. Expect to hear this mantra repeated more and more by Apple in future launches.

This focus on privacy, along with Apple’s aggressive stance on fixing security holes, and defaulting to encryption on its devices, is becoming a clear differentiator between Apple and Android (and let’s face it, in mobile, this is a two horse race, for now).

Finally, Williams concluded the launch by saying Apple wants ResearchKit on as many devices as possible. Consequently, Apple are going to make ResearchKit open source. It remains to see which open source license they will opt for.

But, open sourcing ResearckKit is a very important step, as it lends transparency to the privacy and security which Apple say is built-in, as well as validating Apple’s claim that they don’t see your data.

And it also opens ResearchKit up to other mobile platforms to use (Android, Windows, Blackberry), vastly increasing the potential pool of participants for medical research.

We have documented here on GreenMonk numerous times how Big Data, and analysis tools are revolutionising health care.

Now we are seeing mobile getting in on the action too. And how.