I have been researching and publishing on Cloud Computing for quite some time here. Specifically, I’ve been highlighting how it is not possible to know if Cloud computing is truly sustainable because none of the significant Cloud providers are publishing sufficient data about their energy consumption, carbon emissions and water use. It is not enough to simply state total power consumed, because different power sources can be more, or less sustainable – a data center run primarily on renewables is far less carbon intensive than one that relies on power from an energy supplier relying on coal burning power stations.

At Greenmonk we believe it’s important to get behind the headline numbers to work out what’s really going on. We feel it’s unacceptable to simply state that Cloud is green and leave it at that, which is why we’ve been somewhat disappointed by recent work in the field by the Carbon Disclosure Project. We would like to see more rigour applied by CDP in its carbon analytics.

Carbon intensity should be a key measure, and we need to start buying power from the right source, not just the cheapest source.

I was pleasantly surprised then yesterday when I heard that Google had published a case study ostensibly proving that Cloud had reduced the carbon footprint of at least one major account.

However, it is never that straightforward, is it?

The Google announcement came in the form of a blog post titled Energy Efficiency in the Cloud, written by Google’s SVP for Technical Infrastructure, Urs Hölzle. I know Urs, I’ve met him a couple of times, he’s a good guy.

Unfortunately, in his posting he heavily references the Carbon Disclosure Project’s flawed report on Cloud Computing, somewhat lessening the impact of his argument.

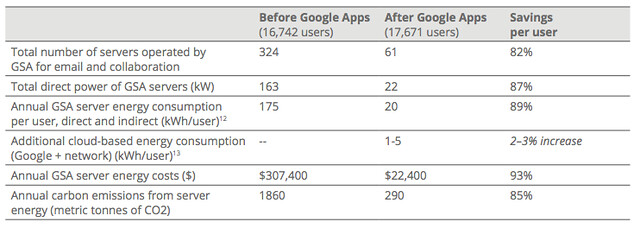

Urs claims that in a rollout of Google Apps for Government for the US General Services Administration,

the GSA was able to reduce server energy consumption by nearly 90% and carbon emissions by 85%.

An 85% reduction in carbon emissions sounds very impressive – but how does Google calculate that figure? Also worth considering is the age of the server estate – any data center that decommissions older servers in favour of new ones is likely to see an efficiency bump. Assuming the GSA servers running Microsoft apps were more than five years old, they would have seen a considerable efficiency bump simply by running the apps on new servers, on premise or off. Without disappearing down a rathole, its also worth noting cradle to cradle factors in server manufacturing – supply chains consume carbon.

We looked at a whitepaper titled Google Apps: Energy Efficiency in the Cloud [PDF], where the search company shares some of the methodology behind the blog post. We would like to see a lot more detail about assumptions and methods.

The key reference to how Google calculated carbon emissions is this line:

The following summary tallies up every GSA server dedicated to email and collaboration across 14 locations in the continental U.S. and applies the appropriate PUEs, electricity prices, and carbon intensities for each location

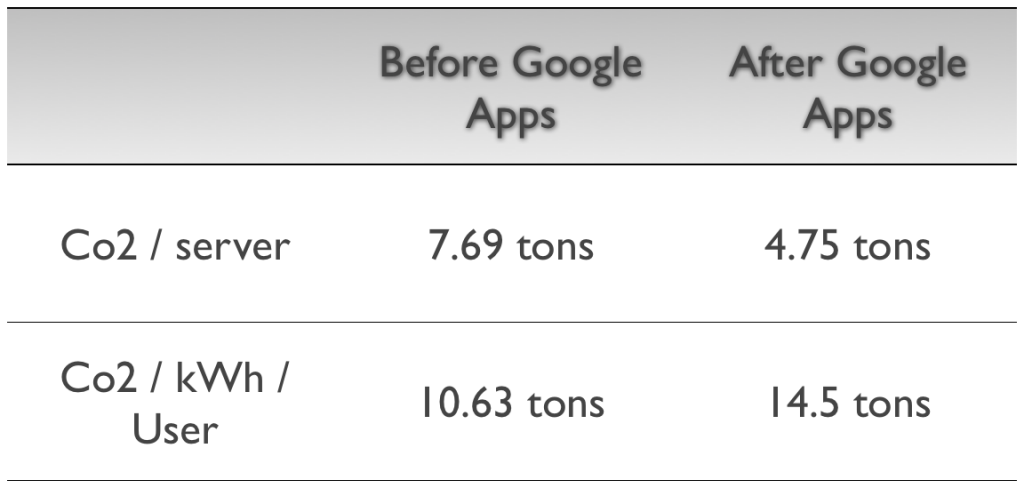

The data in the table above is interesting but if you look at the carbon information, you start to notice something strange – here’s a slightly different view on Google’s data:

While it is no real surprise that Google’s servers produce less CO2 per annum than the GSA’s (4.75 vs 7.69 tons), what is very surprising (to me at least) is the fact that Google’s facilities are significantly more carbon intensive than the GSA’s were (14.5 vs 10.63 tons of CO2 per kWh).

In simple terms, carbon intensity is a measure of the amount of CO2 released in the generation of electricity. The data above, clearly show that the data centres hosting the Google Apps Cloud are not optimised for reduced emissions (the best way for data centers to optimise for reduced emissions is to source electricity generated from renewable sources).

I guess the good news is that, while Google has helped the GSA to reduce its carbon emissions, there’s plenty of room for improvement!

I reached out to Urs for a response to this and because he’s traveling at the minute, the only answer I received pointed out that since 2007 Google’s net emissions are zero. And, in fairness to Google, they do fund some worthwhile offsetting projects, as you can see in the video below (check out the farmer towards the end, he’s just awesome!).

Cloud photo credit mnsc

Follow @TomRaftery